- Home

- Alan Young

In the Footsteps of William Wallace

In the Footsteps of William Wallace Read online

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF

WILLIAM WALLACE

The National Wallace Monument at Abbey Craig. Inset: Bronze statue of William Wallace fixed to the Abbey Craig Monument.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF

WILLIAM WALLACE

IN SCOTLAND AND NORTHERN ENGLAND

ALAN YOUNG & MICHAEL J. STEAD

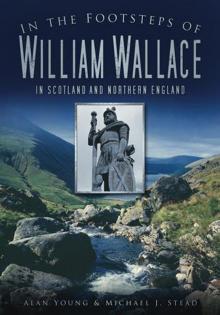

Front cover: The Dryburgh Statue and Selkirk above St Mary’s Loch.

Back cover: The National Wallace Monument at Abbey Craig.

Front endpapers: The Upper Tweed valley and Selkirk Forest.

Back endpapers: Caerlaverock Castle.

First published in 2002

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Text Alan Young, 2002, 2010

© Photographs Michael J. Stead, 2002, 2010

The right of Alan Young and Michael J. Stead to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5143 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1.

WILLIAM WALLACE – THE MAKING OF A LEGEND

2.

PEASANT RASCAL OR NOBLE HERO?

The Stewarts

3.

WILLIAM WALLACE AND THE REVOLT OF 1297

John Balliol

4.

GUERRILLA TO GOVERNOR

The Morays

5.

WALLACE, GOVERNOR OF SCOTLAND

York as a War Capital

Edward I

6.

THE WILDERNESS YEARS – BETRAYAL AND MARTYRDOM

Robert Bruce

APPENDIX: ACCESS TO SITES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

One of the four illustrated plaques found on the Elderslie Wallace Monument. Wallace is seen here leading the Scots at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. The plaques were added to the monument in 1970.

PREFACE

The legends and traditions surrounding William Wallace share common characteristics with those other great legendary figures King Arthur and Robin Hood. All are seen as great leaders fighting for a just cause and their names have become synonymous with heroic resistance to oppression. All three have more legend than history attached to them, and it is these legends that have received great attention and much embellishment through the most powerful modern medium, cinema. The traditions and myths surrounding Arthur and Robin Hood have developed without paying much attention to the historical evidence. William Wallace, on the other hand, can be pinned down historically to the years 1297–1305. Yet, despite this fact, there has been such a tremendous development of legends surrounding William Wallace from the fourteenth century onwards that the historical figure has been almost completely submerged. The layers of this development have recently been fully traced in Graeme Morton’s William Wallace: Man and Myth (Stroud, Sutton Publishing, 2001).

The popularity of Blind Harry’s biography The Wallace (c. 1475) and Mel Gibson’s film Braveheart (1995) has meant that the legendary William Wallace has been fixed ever more firmly in popular consciousness than the historical character and his deeds. Historians must recognise the importance of the development of traditions in their historical contexts as well as continuing to investigate the roots of these traditions. The search for the ‘real’ Arthur and Robin Hood by historians and archaeologists has shed little light on the ‘heroes’ themselves, yet it has revealed a great deal about the world in which Arthur and Robin Hood existed and their legends developed.

Through In the Footsteps of William Wallace Wallace will be examined against the background of recent historical research on both the Scottish political community in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and the nature of Edward I’s ‘direct rule’ over Scotland after 1296. In this context particular questions will be investigated. Was Wallace a loner or merely an agent for his overlords? What was his relationship with the political leaders of late thirteenth-century Scotland – Balliol, Stewart, Comyn and Bruce? Why did he provoke such hostility from Edward I? In addition, is there any historical accuracy in some of those firmly held traditions about William Wallace? History and tradition are equally fascinating elements of the story of William Wallace and here the text and photography reflect both.

The Wallacestone Monument, overlooking Falkirk.

A doorway at Caerlaverock, a key castle to control in Edward I’s campaign in the south-west of Scotland between 1300 and 1304.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A number of individuals and institutions have contributed to the completion of this work. In particular, Professor G.W.S. Barrow’s advice on this topic has been greatly appreciated .and we are particularly grateful for his helpful comments on the book’s final draft. This has helped us to prevent a number of errors and infelicities creeping into the text. The mistakes that remain are entirely our own, as are the opinions contained in the book.

We would like to thank, most heartily, Mrs G.C. Roads, Lyon Clerk and Keeper of the Records at the Court of the Lord Lyon, for her valuable assistance with research on seals. Staff of Historic Scotland were most helpful in sourcing photographs, as were the staff at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Paisley Museum and Art Galleries and the British Library.

We are again most grateful to Joanne Ripley for the speedy and efficient manner in which the final draft was put on disk. Thanks are also due to Jaqueline Mitchell and Alison Flowers at Sutton Publishing for their support for this project, patience and help in seeing it to completion and also to Jo de Vries and Siubhan Macdonald at The History Press.

Alan Young

Michael J. Stead

Dunfermline Abbey has traditional associations with William Wallace’s mother. Blind Harry tells a story of Wallace’s mother fleeing to Dunfermline disguised as a pilgrim.

1

WILLIAM WALLACE – THE MAKING OF A LEGEND

Anyone attempting to understand the William Wallace phenomenon in Scottish history must, first of all, establish how Wallace was viewed by his contemporaries. Only then can it be seen exactly when, how and why the legend and traditions now surrounding this character have evolved and developed over the last 700 years. As part of this process of unfolding layers of history and tradition that most significant source on the life of William Wallace the epic poem The Wallace, written in the 1470s by Henry the Minstrel (better known as Blind Harry), will be closely examined. The Wallace will be set in both the political and cultural context of the day, noting too the sources that had an effect on Blind Harry’s work. In turn it will be seen what impact this late fifteenth-century poem has had on the late twentieth-century film Braveheart (1995) in terms of its portrayal of William Wallace. A number of questions arise. Why has Blind Harry’s view of Wallace remained such a powerful, indeed dominant, influence on the popular perceptions of William Wallace? What other interpretations are there and why have these re

mained in the background? How far does this accepted view of William Wallace distort what is known of the historical Wallace?

Contemporary evidence for the historical William Wallace is restricted narrowly to the years between his sudden emergence onto the military scene in 1297 and his death in 1305. Within this time information is unevenly spread. Most material relates to the period from the summer of 1297, just before his triumph over the English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge (11 September 1297), until shortly after his defeat at the Battle of Falkirk (22 July 1298). It is to these years that the only four historical documents emanating from William Wallace himself belong. After defeat at Falkirk, Wallace left Scotland, acting as a roving ambassador for the Scottish cause, principally at the French and papal courts between 1298 and 1302. Little is known in detail of his activities during these years. Following his return to Scotland in late 1302 or early 1303, Wallace can be traced only through fragmentary references to his appearance in skirmishes with the English and in reports of Edward I’s efforts to capture him. This pursuit ended with Wallace’s capture by John of Menteith in 1305, after which Wallace was taken south to London where he was tried and executed. Reports of Wallace’s trial and savage death form the bulk of the surviving contemporary comments on him.

The Braveheart Statue. This representation of Mel Gibson as William Wallace was placed in the car park of the National Wallace Monument in 1998. It is the work of Tom Church and is a reminder of how significant Mel Gibson’s film Braveheart has been in the development of the Wallace legend.

One very interesting aspect of contemporary evidence on William Wallace is how little emanates from Scottish sources. The main Scottish strand in the standard narrative of Scottish medieval history was John of Fordun, whose Chronicle of the Scots Nation was compiled in the 1380s. Though written long after Wallace’s death, Fordun’s Chronicle is now acknowledged as an invaluable source of information for the period of William Wallace’s influence. He had access to original thirteenth-century material and therefore must be recognised as the closest Scottish source to Wallace himself. Yet, though Fordun’s reporting of facts may be accurate, his interpretation of events was naturally affected by the politics of his time. After Robert Bruce’s (King Robert I’s) death in 1329, Scotland had endured some years of great political instability – there had been a minority period, civil war and the constant threat of English invasion to support Edward Balliol’s attempt to gain the Scottish throne. All of these threats to the Scottish situation seemed to be replicating the events that followed the death of Alexander III in 1286 which led to Edward I’s interference in Scottish affairs. To make matters worse, the Scottish King David II had been captured by the English at Neville’s Cross (near Durham) in 1346 and was subsequently held in lengthy captivity. As a result of these circumstances, Fordun’s narrative strongly emphasises three themes – the growth of the Scottish nation and patriotism, the cause of Scottish independence and the importance of the Scottish monarchy in supporting these objectives. In view of the latter point, it is hardly surprising that Fordun’s chief hero was Robert Bruce, who restored an independent Scottish monarchy in 1306, rather than William Wallace.

The Kinghorn Monument. This monument to King Alexander III, who died mysteriously on 18 March 1286 while travelling in a storm from Edinburgh to Kinghorn in Fife, is a reminder of the political uncertainty in Scotland during William Wallace’s early years.

When Fordun’s text is examined for information on William Wallace, he gives only a framework for his activities, an outline of his actions with little material about his background and, interestingly, in respect to later writings, nothing on his appearance. Undoubtedly, William Wallace was a hero, as can be seen in the following extract:

The Abbey Craig Monument, close to the scene of his great triumph at Stirling Bridge, features this bronze statue of Wallace in chain mail holding aloft a huge sword.

From that time there flocked to him all who were in bitterness of spirit and were weighed down beneath the burden of bondage under the unbearable domination of English despotism, and he [Wallace] became their leader. He was wondrously brave and bold, of goodly mien and boundless liberality . . .

However, to Fordun Robert Bruce was the hero of his Chronicle. Significantly, Fordun makes no connection between Wallace and Bruce in his narrative – they acted quite separately.

Though there are the beginnings of hero-worship contained within Fordun’s descriptions of Wallace’s actions, these can hardly be considered the foundations of a legend. Ironically, it is to contemporary English sources that the historian must go to gain not only more details of Wallace’s activities but also to trace the origins of the legend. Foremost among these English sources are two northern chronicles, the Guisborough Chronicle (North Yorkshire) and the Lanercost Chronicle (Cumbria), while the annals of Peter Langtoft, which derive from Bridlington, are also of use. All English material is biased against William Wallace, targeting him as a hate figure. This surely reflects Edward I’s attitude to Wallace at the time – to the English King Wallace came to symbolise, in 1297 and 1298, the spirit of the Scottish opposition and this became even more apparent between 1303 and 1305 when most Scottish resistance was crumbling away. It is interesting, if hardly surprising, that the most extreme English anti-Wallace sentiments were expressed by chroniclers living much further south, such as William Rishanger (St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire), Nicholas Trivet (Oxfordshire), Matthew of Westminster and the Norwich monk Bartholomew Cotton. The anonymous author of the poem Song on the Scottish Wars shared their opinions too. Whatever the degree of hostility shown towards Wallace by contemporary English sources, there was a common desire generally to discredit Wallace’s reputation both during his life and after his execution. To the Guisborough chronicler, Wallace was ‘a common thief . . . a vagrant fugitive’. To the Lanercost chronicler he was ‘a bloody man . . . who had formerly been a chief of brigands’. Within the Lanercost Chronicle was published a song describing Wallace:

Thou pillager of many a holy shrine

Butcher of thousands, threefold death be thine

Similar views, if more extreme, were voiced by Matthew of Westminster, who referred to Wallace as:

. . . a man void of pity, a robber given to sacrilege, arson and homicide, more hardened in cruelty than Herod, more raging in madness than Nero . . .

The anonymous author of the political song On the Execution of Sir Simon Fraser pointed to Edward I’s motives in using Wallace’s death as a lesson to the Scots:

Sir Edward our king, who is full of piety

sent the Wallace’s quarters to his own country

to hang in four parts (of the country) to be their mirror

thereupon to think, in order that many might see and dread

The targeting of Wallace as a hate figure and the triumphalism of England’s popular songwriters at his death probably had the opposite effect to that intended. Instead of destroying Wallace’s reputation, it heightened it, made Wallace a martyr for the Scottish cause and helped to create the legend of his life and deeds.

In Scotland it was not until the fifteenth century that the successors and amplifiers of John of Fordun began to promote a more detailed picture of William Wallace as patriot hero. The Scottish enhancers of Wallace’s reputation were, principally, Andrew Wyntoun – Oryginale Cronykil of Scotland (c. 1420), Walter Bower – Scotichronicon (c. 1440) and most famously Henry the Minstrel (Blind Harry) – the vernacular poem The Wallace (1470s). It is clear that well before The Wallace was written there were tales, or ‘gestis’, circulating about William Wallace. Andrew Wyntoun comments:

Of his good deeds and his manliness

Great Gestis, I heard say, are made . . .

Whoever his deeds would all endite

Would need a mighty book to write

Unfortunately, no traces of these ‘gestis’ have been discovered.

Dunfermline Abbey, famous as the burial place of Robert Bruce and other Scottish ki

ngs, contains this very fine stained-glass window showing Wallace, bearing a sword and guarding Scotia (represented by a young woman), with Bruce, St Margaret and Malcolm Canmore.

In the hands of Scottish chroniclers of the fifteenth century, William Wallace became a strongly Christian figure. Walter Bower, Abbot of Inchcolm, describes Wallace:

Moreover the Most High had distinguished him and his changing features with a certain good humour, had so blessed his words and deeds with a certain heavenly gift . . . a most skilful counsellor, very patient when suffering, a distinguished speaker who above all hunted down falsehood and deceit and detested treachery; for this reason the Lord was with him and with His help he was a man successful in everything . . . with veneration for the church and respect for the clergy, he helped the poor and widows, and worked for the restoration of wards and orphans bringing relief to the oppressed. He lay in wait for thieves and robbers, inflicting rigorous justice on them without any reward. Because God was greatly pleased with works of justice of this kind, He in consequence guided all his activities.

This clearly demonstrates that Wallace was well on the way to unofficial canonisation before Blind Harry’s biography in the 1470s. It is rather ironic to compare contemporary English descriptions of Wallace as ‘a common thief’ and ‘pillager of many a holy shrine’ with the depiction of him as an exalted Christian hero in the fifteenth-century Scottish chronicles.

Another of the plaques mounted on the Elderslie Wallace Monument. Wallace is seen here raising the Scottish standard.

Walter Bower not only portrays Wallace as a paragon, he also provides the first detailed physical impression of Wallace. This too is a prestigious, classical portrait:

In the Footsteps of William Wallace

In the Footsteps of William Wallace